Whether you’re building a house, crafting up some do-it-yourself holiday gifts, or even putting together a plastic model airplane kit, there inevitably are assembly milestones you reach that are considerably more satisfying to reach than others.

They are the kind of moments that prompt you to reflect on your work so far, bask in the glow of your accomplishment, and be inspired to continue toward the end so you can see how what you once only envisioned on paper has become reality.

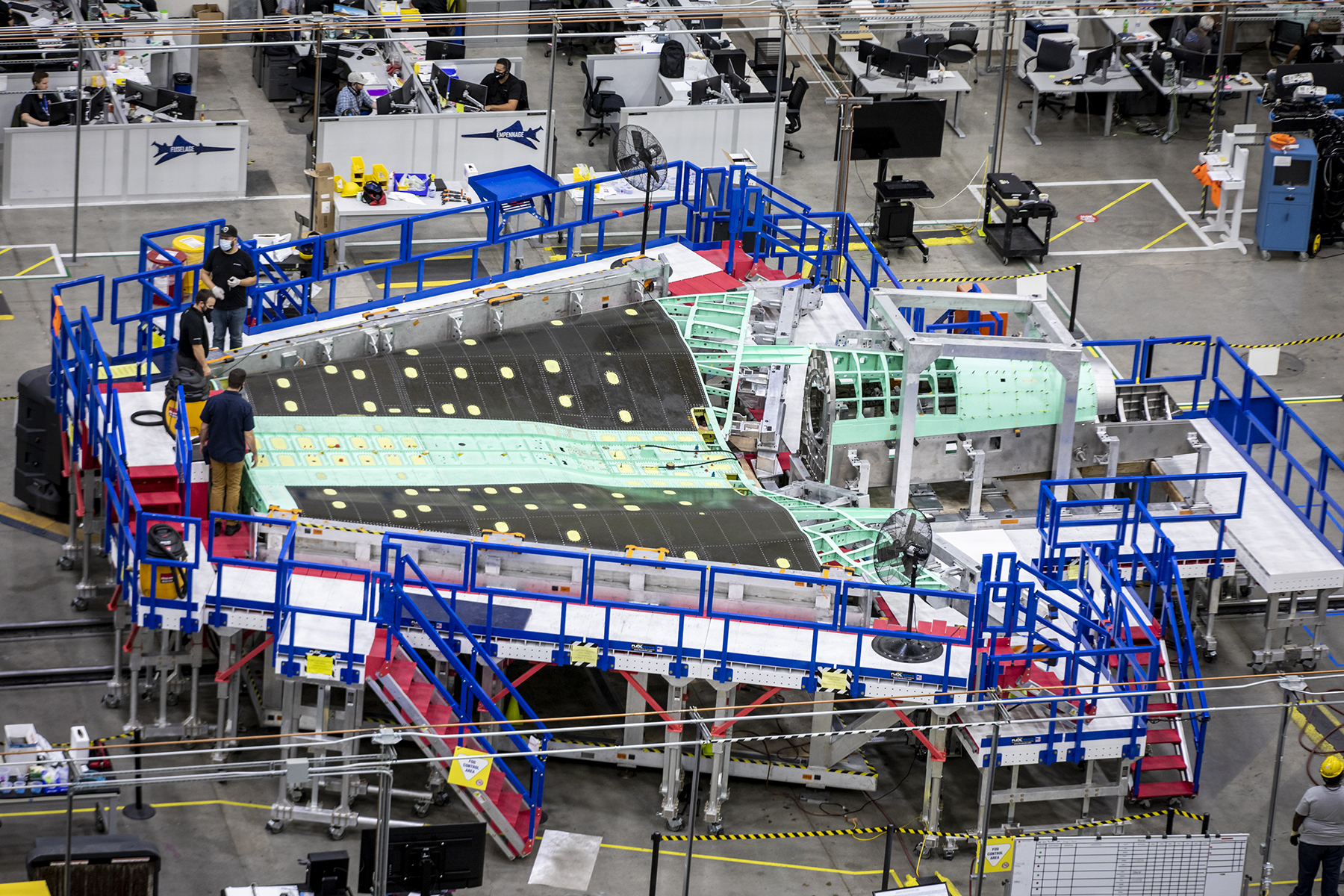

Such a key milestone moment was reached Nov. 5 for the team putting together NASA’s X-59 Quiet SuperSonic Technology airplane at Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works factory in Palmdale, California.

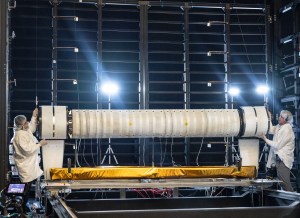

On that day technicians finished major work on the wing, closing up parts of the wing’s interior that will serve as the airplane’s fuel tanks and are intended to never be touched again by human hands.

“The fact this is the first time we’ve reached a milestone like this in which we won’t see these parts or have access to this area again is why this is so important to us. It reminds us the X-59 really is coming together,” said Steve Macpherson, a senior Lockheed Martin manager.

Macpherson leads the Lockheed Martin team building the X-59 under a $247.5 million contract with NASA.

The fact the wing has hit this milestone in its assembly – the first major system of the airplane to do so – now allows other key components of the airplane including the fuselage and tail assembly to be joined together. The company is targeted to finish assembly, conduct test flights, and deliver the plane to NASA between now and sometime during 2023.

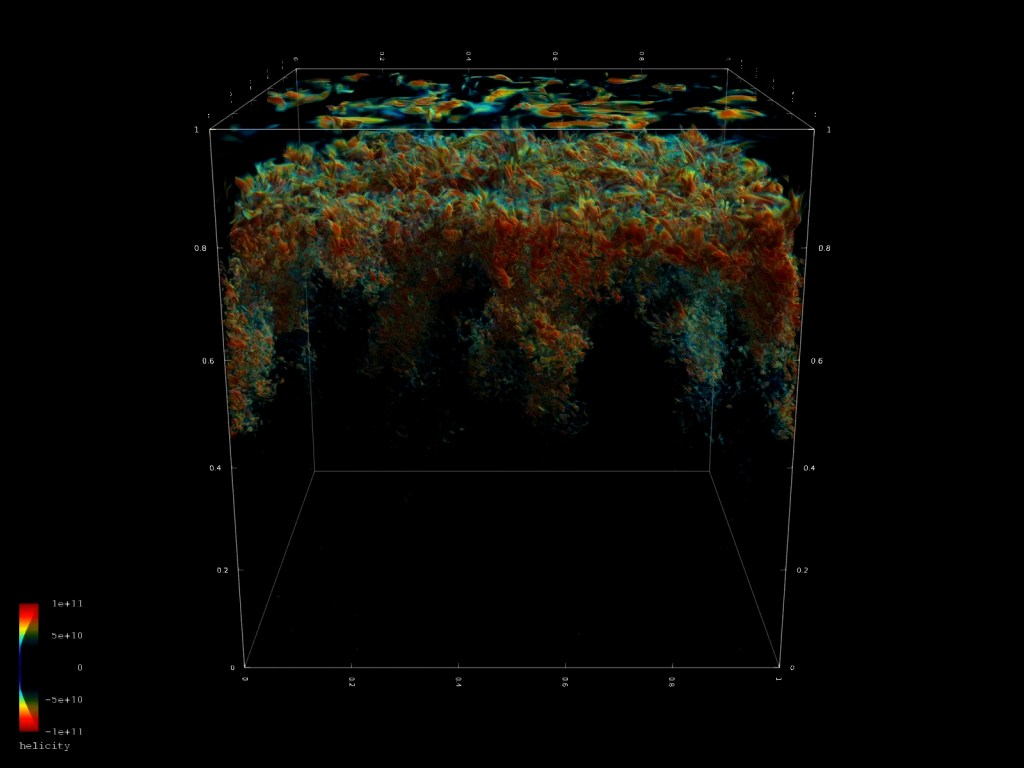

The X-59 is designed to generate supersonic sound waves that are so quiet people on the ground will hear them as sonic thumps – if they hear anything at all. Eventually, the X-59 will be flown over select communities to measure public perception of the sound.

Results will be given to regulators to use in determining new rules that could allow commercial faster-than-sound air travel over land.

The airplane’s shape is the key to its low booms and a large part of that shape is reflected in the contours of the X-59’s wing, especially its lower surface. Yet while the physics behind the wing’s shape is complex, assembling the wing itself was more-or-less straightforward.

But that doesn’t mean it was easy. The wing – indeed, the entire airplane – isn’t being built as part of some mass production factory line. Instead, the assembly process resembles something more akin to a hand-crafted work of art.

“Great care had to be taken to ensure the wing skins were precisely in the position, orientation, and smoothness as designed so the wing’s shape will help produce the intended low boom,” Macpherson said.

“We went through multiple checks to verify the engineering requirements had been met and that the fuel tanks were sealed properly and would hold pressure. Then, just prior to final installation of each skin to close the fuel bays, we put at least four sets of eyes in each bay to ensure nothing was left behind that wasn’t supposed to be there,” he said.

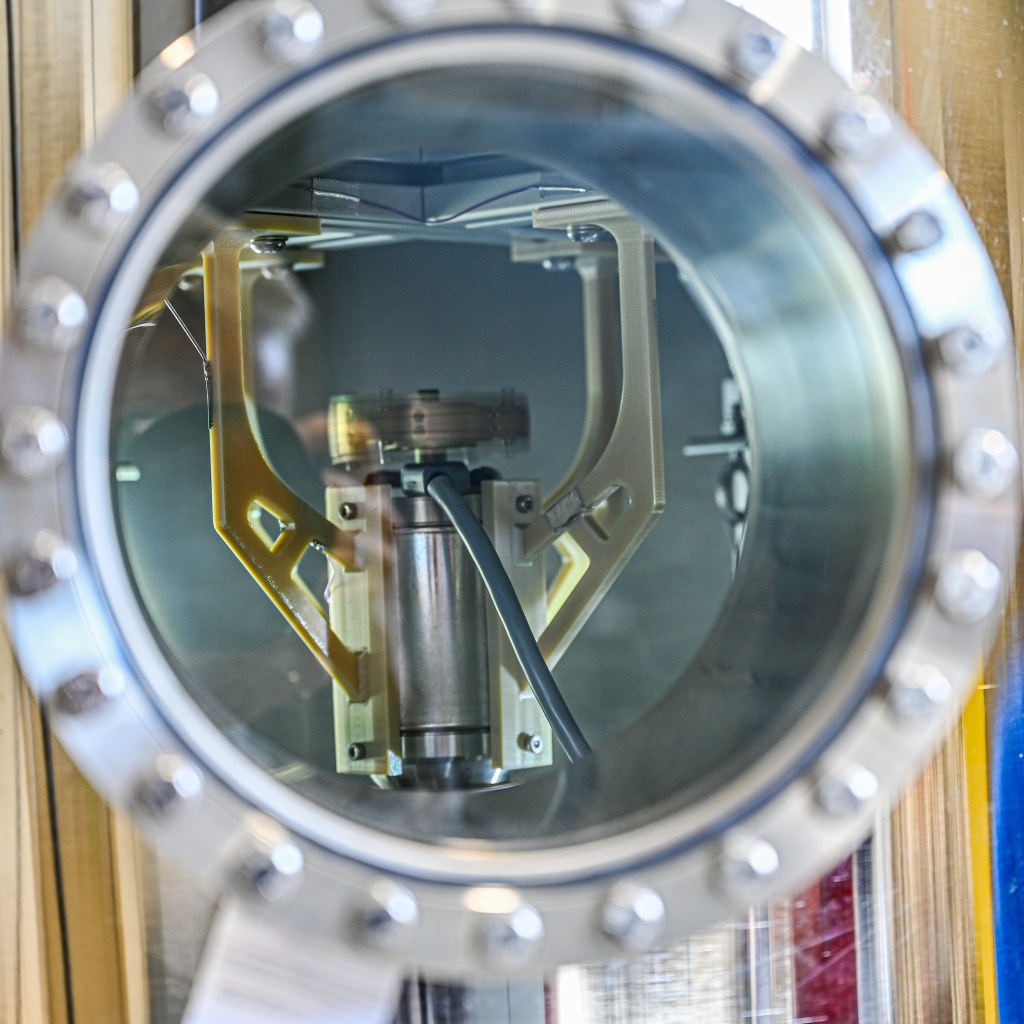

Manufacturing the composite wing surfaces to a precise shape and attaching them to the spars that make up the wing’s interior framework was aided to great effect by robotic systems with names like Mongoose and COBRA.

“That’s a kind of perfect combination of names, right?” said Jay Brandon, NASA’s chief engineer for the project office responsible for the X-59. “These systems have been of great help to the construction by being able to do things precisely, over and over again.”

For example, Mongoose is a commercially available tool Lockheed Martin used to layup the composite wing skins with their complex geometry, a process that took full advantage of the device’s ability to work in five directions and use ultraviolet light to bond the composite material as it moved along.

Meanwhile, COBRA – which is short for Combined Operation: Bolting and Robotic AutoDrill system – could automatically produce the holes that allowed the skins to be attached to the wing’s frame. Normally a labor-intensive process that took time, COBRA only needed about 20 seconds to create each of the thousands of needed holes.

Time and labor savers like COBRA have been particularly valuable given the X-59’s one-of-kind nature compounded by a global pandemic interfering with workforce scheduling and availability, Brandon said.

“The first time you build an airplane, even though it’s ‘just’ an airplane, there’s lots of challenges in getting all the parts to fit the way they should. And there’s always the human element where somebody has a problem that has to be solved,” he said.

Brandon noted that Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works philosophy, which keeps those who design and those who build working closely together, has worked well and kept NASA in the loop at every step – all of which made the wing-related milestone possible.

“It’s not just NASA looking over a Lockheed shoulder trying to find errors. It’s watching what’s going on, making suggestions, and being part of the team. It’s been really great, and I think it’s a very successful process,” Brandon said.

That process will continue as the X-59 team pushes to the next major milestone, which is expected late in the summer of 2021 when the essentially finished airplane – minus its single GE jet engine – will be taken by land to Texas for a series of structural tests.

Then it will be back to California for the final, final assembly, a paint job, and roll out leading to the initial test flights.

For now, the troubled year of 2020 is ending on a high note for everyone associated with the X-59 in the high desert of California.

“This was a significant win for the team and win for the program to see the successful close out of this wing tank portion of the wing,” Macpherson said.